It is an iconic image of the Australian goldfields – seemingly offering proof that hard work and good luck could bring vast wealth for anyone willing to have a go.

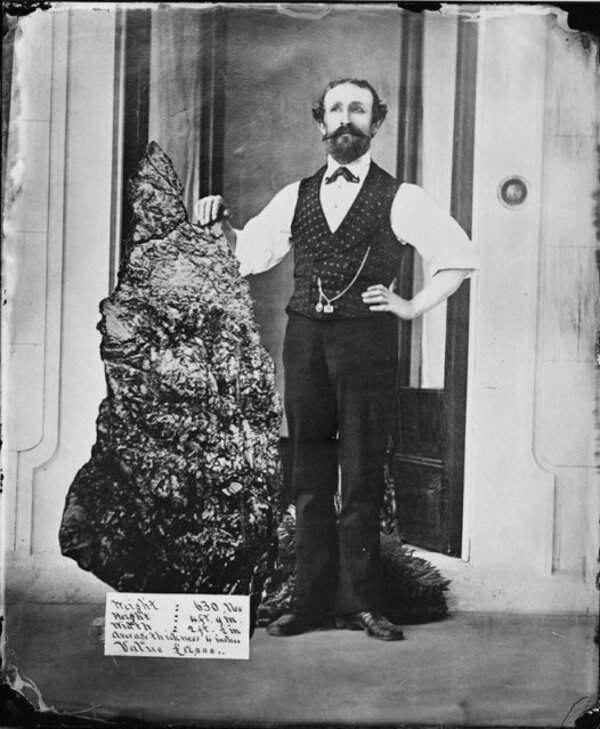

This famous picture of industrious German immigrant Bernard Holtermann posing with the largest gold ‘nugget’ ever found is also an elaborate fake.

While the Holtermann gold – all 93kg of it – was real, its part-owner was never actually photographed standing proudly with the lump of rock outside his home.

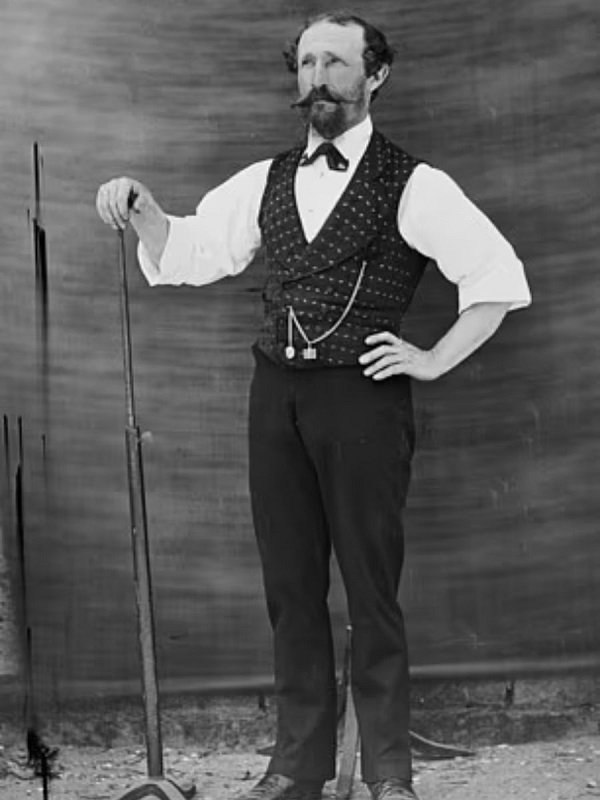

Instead, the picture is a montage of at least four superimposed images in a crude 19th century version of photoshop.

There is the nugget itself, the goldminer resting his hand on an iron support, and the verandah of his house. Holtermann’s head, facing the viewer, appears to have been pasted on.

This famous picture of industrious German immigrant Bernard Holtermann posing with the largest gold ‘nugget’ ever found is an elaborate fake. While the Holtermann gold – all 93kg of it – was real, its part-owner was never actually photographed standing proudly with the lump of rock outside his home

The picture is a montage of at least four superimposed images in a crude 19th century version of photoshop. There is the nugget itself, the gold miner resting his hand on an iron support, and the verandah of his house. Holtermann’s head, facing the viewer, has been pasted on

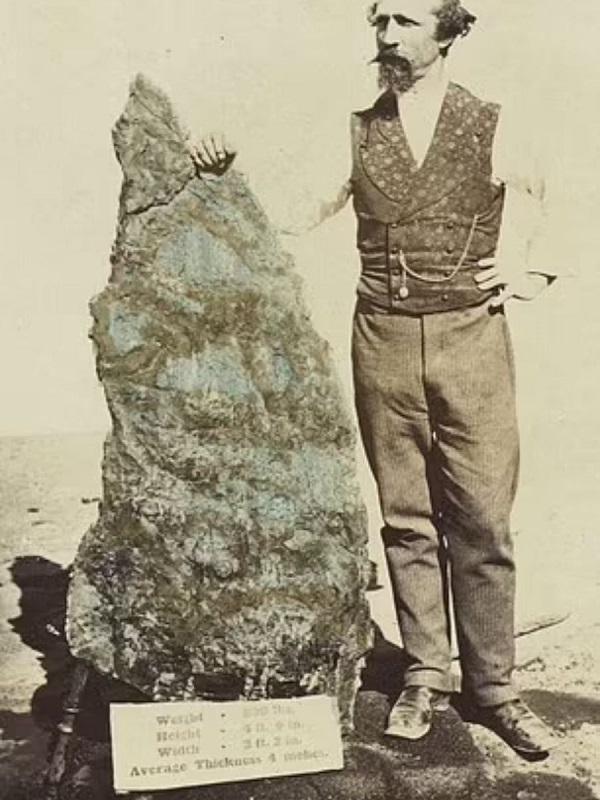

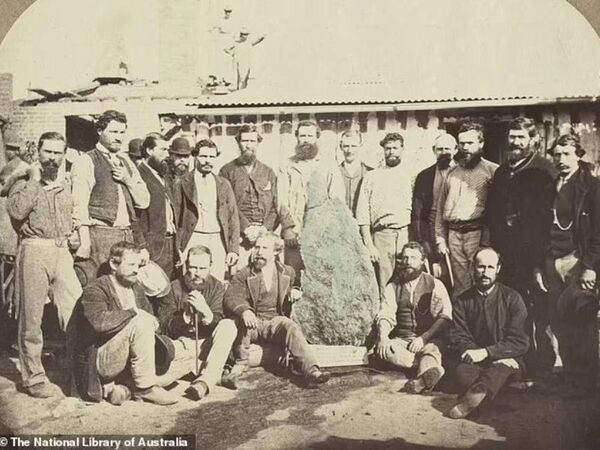

The story behind the photograph is almost as intriguing as the record gold discovery made by Holtermann’s mining company in 1872 and the tale of the man himself. A group of men including Holtermann (left of the nugget) is pictured at Hill End in 1872

The story behind the photograph is almost as intriguing as the record gold discovery made by Holtermann’s mining company in 1872 and the tale of the man himself.

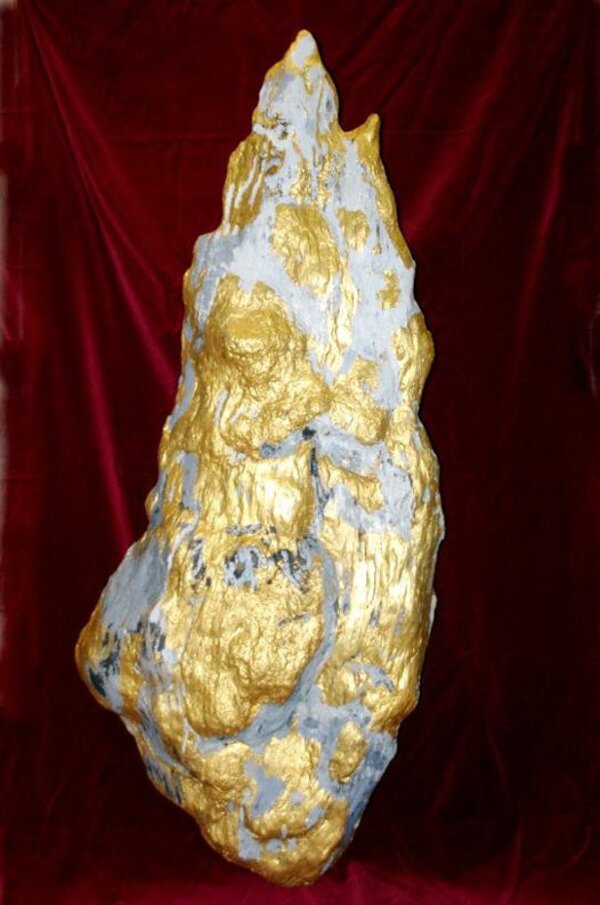

‘Holtermann’s Nugget’ was not really a nugget at all. It was a mass of gold, quartz and slate broken from a quartz reef, correctly called a specimen or matrix.

It was discovered about 2am on October 19, 1872 in the Star of Hope mine on Hawkins Hill at Hill End, about an hour’s drive north of Bathurst in the Central Tablelands of New South Wales.

Star of Hope partners Holtermann and Louis Beyers had struck rich seams of the precious metal the previous year; now they had found a wall of gold which brought them almost instant fame and a considerable fortune.

The 285kg specimen pulled from the mine measured 144.8cm by 66cm by 10.2cm and contained 93kg (3,000 troy ounces) of gold which today would be worth more than AUD$7million.

Holtermann wanted to buy the specimen outright but his shareholders had already booked time at the local stamper battery for the next week and after being photographed it was crushed and melted down.

Holtermann had a 45cm diameter stained glass window featuring a representation of him with the nugget installed in his Sydney home, which is now part of Church of England Grammar School. The window is pictured

The Australian Museum holds a replica of the Holtermann nugget which was restored in 2017. The museum’s collection manager for mineralogy Ross Pogson is pictured in Holtermann’s pose

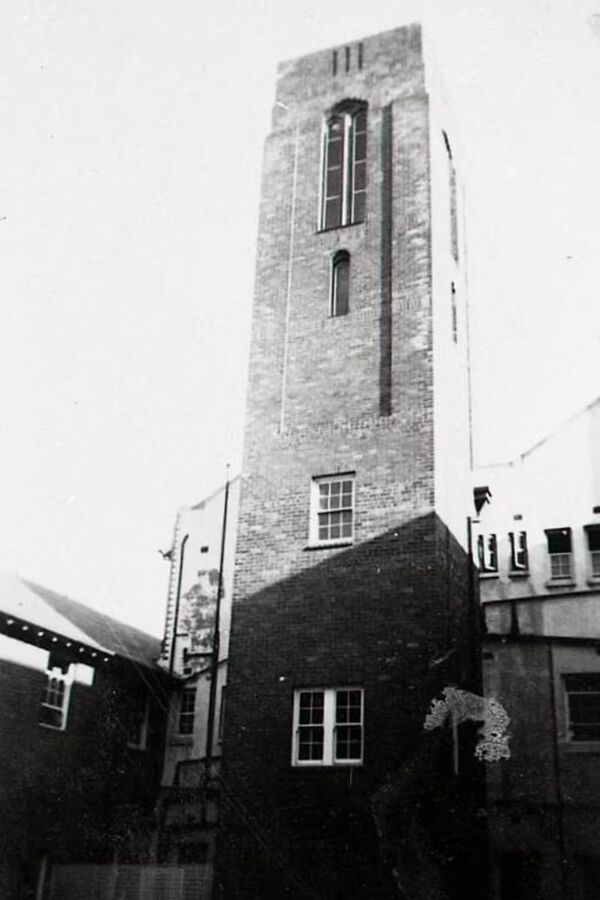

His share of the proceeds allowed Holtermann to build a mansion at St Leonards on Sydney’s lower north shore with a distinctive square tower overlooking the harbour.

From the tower, Holtermann indulged his passion for photography, helping take enormous panoramic pictures of Sydney which were exhibited around the world.

He also commissioned a comprehensive photographic record of NSW and Victorian goldfields which was uncovered 80 years later when thousands of glass negatives were found in a garden shed.

Holtermann was elected to the NSW Parliament and his mansion, known as The Towers, would eventually be subsumed into Sydney Church of England Grammar School, better known as Shore.

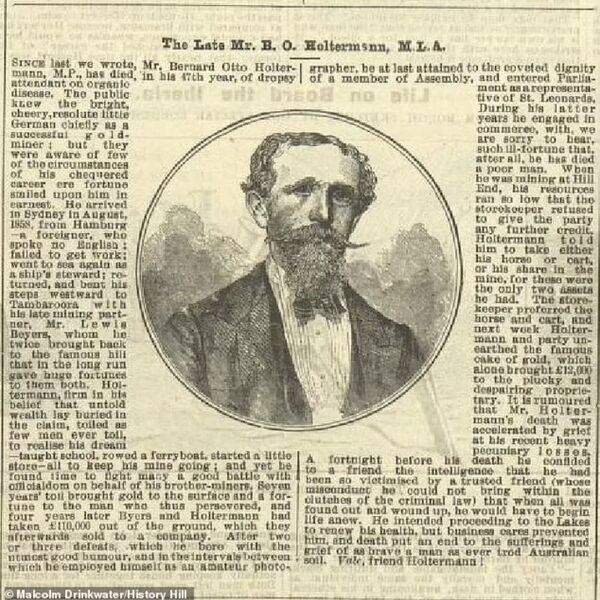

Upon his death, The Bulletin noted: ‘The public knew the bright, cheery, resolute little German chiefly as a successful goldminer… ‘

‘But they were aware of few of the circumstances of his chequered career ere fortune smiled upon him in earnest.’

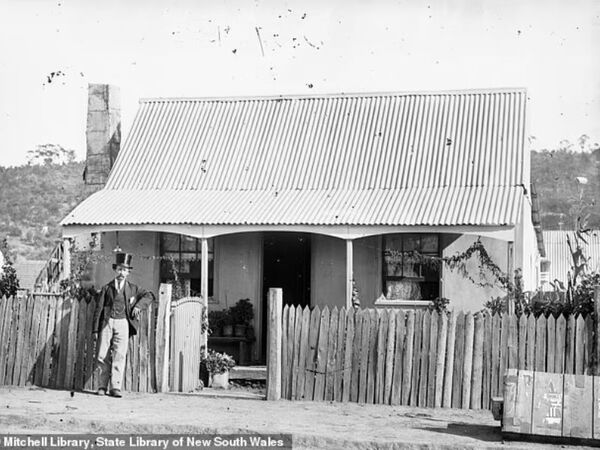

‘Holtermann’s Nugget’ was not really a nugget at all. It was a mass of gold, quartz and slate broken from a quartz reef, correctly called a specimen or matrix. Holtermann is pictured outside his home in Tambaroora Street, Hill End

Holtermann used his share of the proceeds from his record find to build a mansion at St Leonards on Sydney’s lower north shore (pictured). Holtermann indulged his passion for photography from a distinctive square tower overlooking the harbour

Holtermann was elected to the NSW Parliament and his mansion, known as The Towers, would eventually be subsumed into Sydney Church of England Grammar School, better known as Shore. The tower was encased in brick in 1934. it is pictured in 1940

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann was born in Hamburg on April 29, 1838 and sailed from his homeland to avoid military service in 1858, arriving in Melbourne early the following year.

After working for several months as a waiter at the Hamburg Hotel in the city he met Polish miner Ludwig Hugo Beyers. The pair went prospecting on the Hill End-Tambaroora fields, where gold had been discovered in 1851.

Holtermann and Beyers began mining their Star of Hope claim in 1861 but had little early success. Their company was listed on the stock exchange and ownership of the mine would expand to eight shareholders.

Forced to try other business ventures, Holtermann was licensee of the All Nations Hotel at Hill End by 1868, the same year he and Beyers married sisters in Bathurst.

Rich veins of gold found in Star of Hope in 1871 were soon exhausted and new partner Mark Hammond sank a fresh shaft the following year without his partners’ authority.

Within weeks that shaft hit another gold-bearing seam but Hammond sold his stake in the mine shortly before the other shareholders struck their real bonanza.

Bernhardt Otto Holtermann was born in Hamburg on April 29, 1838 and sailed from his homeland to avoid military service in 1858, arriving in Melbourne early the following year

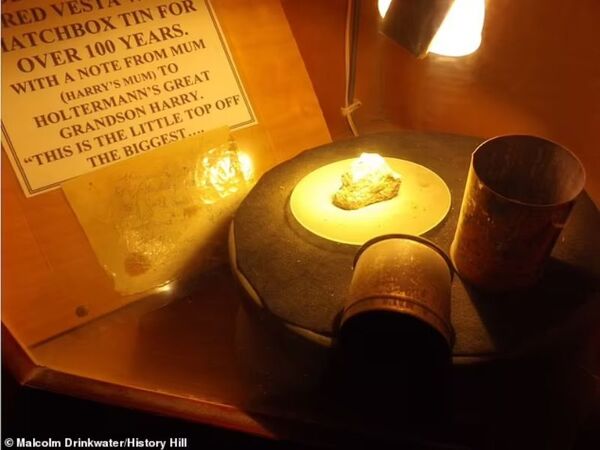

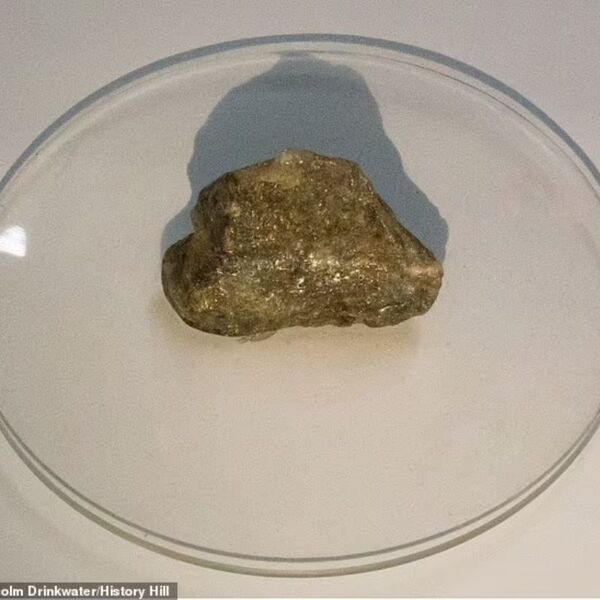

Before the specimen was crushed, Holtermann, the mine’s manager, chipped off the tip as a souvenir. That chip is now held by History Hill Museum at Hill End near Bathurst (pictured)

The largest single mass of gold ever recorded on earth was brought to the surface and Holtermann commissioned itinerant photographer Beaufoy Merlin to capture him next to the find.

Before the specimen was crushed, Holtermann, the mine’s manager, chipped off the tip as a souvenir.

Five months after Holtermann’s Nugget was found an even larger specimen, estimated to contain 155kg (5,000 troy ounces), was recorded in the Star of Hope’s day book.

The miners broke it up underground rather than manhandling another huge rock to the surface where it would be crushed and smelted anyway.

The second, broken, mammoth specimen was described in one newspaper report of February 1873 as having been displayed for a week before being crushed.

Holtermann wanted others to share in his wealth and enlisted Merlin and his partner Charles Bayliss to photograph the NSW and Victorian goldfields so he could promote Australia to the world.

Holtermann and Louis Beyers began mining their Star of Hope claim in 1861 but had little early success. Their company was listed on the stock exchange and ownership of the mine would expand to eight shareholders. Holtermann (left) and Beyers are pictured

A replica of the Holtermann specimen (left) was displayed in the Australian Museum up until the early 1970s. It was restored in 2017 with gold, white and blue-grey paint (right)

He built a studio for the pair’s American & Australasian Photographic Company at Hill End and set them the task of producing images for what he would bill as Holtermann’s International Travelling Exposition.

The photographic process of the time required coating glass plates with a wet emulsion before use and development immediately afterwards.

Using a portable darkroom, Merlin and Bayliss documented the Hill End and Gulgong goldfields but Merlin died of pneumonia in September 1873, leaving Bayliss to finish photographing Victoria’s gold towns.

Holtermann was now one of the richest men in the colony and gave up prospecting to moved to Sydney, where he bought an estate above Lavender Bay.

There he made substantial additions to an existing house, notably adding a central 27m tower on each side of which displayed his name in large capital letters.

Within the tower was a 45cm diameter stained glass window featuring a representation of the famous picture of Holtermann with the ‘nugget’.

A few months after Holtermann’s nugget was found an even larger specimen, estimated to contain 155kg of gold was recorded in the Star of Hope’s day book. The miners reportedly broke it up underground. Holtermann, second from left, is pictured with the pieces

Holtermann sketched the pieces of a gold specimen found in his Star of Hope mine five months after the record-breaking mine. The second, broken, specimen was described in one newspaper report of February 1873 as having been displayed for a week before being crushed

The mansion was shown on maps as The Towers but was colloquially known as Holtermann’s Tower, or Holtermann’s Folly.

It drew attention throughout the colony and was described in the Singleton Argus as an ‘architectural ornament to the locality in which it is situated’ and ‘a residence fit for a nobleman.’

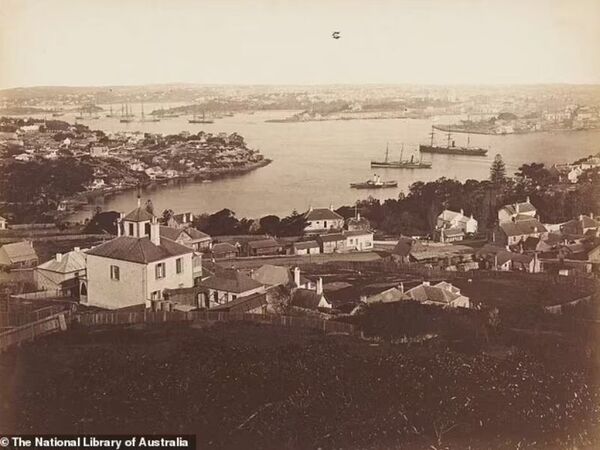

The tower was the perfect vantage point from which to realise Holtermann’s next ambition to photograph the entire magnificence of Sydney for an international audience.

With Bayliss he made enormous glass plate negatives which measured 152cm by 91cm and began photographing the harbour and surrounding suburbs.

Perched in the tower, Holtermann and Bayliss completed a 9.78m panorama comprised of 23 images which Holterman claimed formed the largest photograph in the world.

It was awarded a bronze medal at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, where Holtermann sold copies and presented lectures on the attractions of Sydney.

The tower of Holtermann’s home was the perfect vantage point from which to realise his ambition to photograph the entire magnificence of Sydney for an international audience. This view over Lavender Bay and Milsons Point was taken from the tower

In the early 1930s the original Holtermann house facade was in a state of disrepair. Due to financial constraints brought on by the Depression the school had two choices: brick over the structure or demolish it. The school chose to brick over the building, including the tower

The Philadelphia exhibition attracted almost 10 million visitors and 13 million more attended the Paris Exposition Universelle Internationale in 1878 when the panorama won a silver medal.

World’s three largest genuine gold nuggets

Welcome Stranger Nugget: 99.9kg (3,524oz). Found by English prospectors John Deason and Richard Oates in February 1869 at Moliagul in Victoria. Broken into three pieces and melted down.

RNC Minerals’ 1 Nugget: 94.9kg (3,351oz). RNC Minerals found the gold-encrusted rock at the Beta Hunt mine in Western Australia in September 2018.

Welcome Nugget: 68.9kg (2,433oz). Found in Ballarat, Victoria, by miners from Cornwall, England in June 1858. Bought by the Royal Mint and melted down into sovereign coins.

Source: goldindustrygroup.com.au

Holtermann travelled through France, Germany and Switzerland, showing his photographs and answering inquiries about life in Australia, before coming home.

That mission accomplished, In retirement he wrote papers and came up with formulae for medicines, producing Holterman”s Life Preserving Drops.

He was elected to the NSW Legislative Assembly as the member for St Leonards in 1882 at his third attempt and served in parliament for the last years of his life.

Holtermann suffered cancer of the stomach, cirrhosis of the liver and dropsy (a build up of fluid in the body’s tissue which is also known as oedema) and died in 1885 on his 47th birthday.

The Bulletin recorded his death was accelerated by a number of disastrous business ventures and the deceitful dealings of a trusted friend which left him a poor man.

‘Death put an end to the sufferings and grief of as brave a man as ever trod Australian soil,’ its unnamed writer concluded. ‘Vale, friend Holtermann.’

He was buried in St Thomas’s Cemetery at Crows Nest, leaving behind wife Harriet, three sons and two daughters. But his story was not over.

The Towers was bought by Holtermann’s neighbour Thomas Dibb who sold it in 1888 to the Church of England and it became part of Shore when the school opened the following year.

Holtermann’s negatives were largely forgotten for decades until a remarkable discovery in 1951 usually credited to photographer and journalist Keast Burke.

Holtermann died in 1885 on his 47th birthday. He was buried in St Thomas’s Cemetery at Crows Nest, leaving behind wife Harriet, three sons and two daughters

The Bulletin recorded Holtermann’s death had been accelerated by a number of disastrous business ventures and the deceitful dealings of a trusted friend which left him a poor man. ‘Death put an end to the sufferings and grief of as brave a man as ever trod Australian soil’

Burke, the New Zealand-born editor Australasian Photo-Review, traced the plates to the home of the widow of Holtermann’s youngest son Leonard at 15 Thomas Street, Chatswood.

There, in what Burke described as like opening Tutankhamun’s tomb, he found about 3,500 negatives safely stored in a locked garden shed.

‘After some delay, a key was obtained through the cooperation of her son Bernard Holtermann III, and the room disclosed its long-hidden treasures,’ Burke later wrote.

‘It was an incredible sight: neat stacks of cedar boxes of various dimensions, each with slotted fittings which had held the large negatives in perfect preservation.

‘And there were the actual negatives of the huge 1875 Harbour panorama, noted in all the records of photography as being the largest ever taken by the wet-plate process.’

More than a century after the world’s largest gold specimen was dug from the earth, Holtermann’s great grandson produced the chip that had been knocked off the top, which he had kept in a tin under his bed. The tin is pictured

Harry Holtermann, who is still alive, sold the chip taken by his great grandfather to Hill End’s History Hill Museum where it remains on display with other artefacts linked to his ancestor

Harry Holtermann’s mother gave him a note when she passed down the piece of his great grandfather’s nugget. ‘This is the little top off the biggest nugget of gold Holtermann found at Hill End’

The negatives’ subjects ranged from views taken around Sydney and Melbourne to detailed portraits of frontier life in the Hill End and Gulgong goldfield settlements.

Upon Burke’s recommendation the hoard was donated to the State Library where in 2011-2012 they were cleaned, rehoused and rescanned.

The Holtermann Collection is now considered one of the world’s great photographic records and is on the register of the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World.

Holtermann’s legacy lives on in a street at Crows Nest named after him and a replica of his nugget sat outside Bathurst Regional Council until it was vandalised last year.

The Australian Museum also holds a resin and fibreglass facsimile of the nugget which after decades of neglect was restored with gold, white and blue-grey paint in 2017.

A copy of Holtermann’s harbour panorama is hung in the hallway that leads to North Sydney Council’s customer service centre, above a comparable modern image (pictured)

Holtermann’s tower, which was encased in brick in 1934, is still part of Shore School and is now within the building known as School House which accommodates boarders

A copy of Holtermann’s harbour panorama is hung in the hallway that leads to North Sydney Council’s customer service centre, above a comparable modern image taken by photographer Christopher Shain.

More than a century after the world’s largest gold specimen was dug from the earth, Holtermann’s great grandson produced the chip that had been knocked off the top, which he had kept in a tin under his bed.

Harry Holtermann, who is still alive, sold the chip to Hill End’s History Hill Museum where it remains on display with other artefacts linked to his ancestor.

Holtermann’s tower, which was encased in brick in 1934, is still part of Shore School and is now within the building known as School House which accommodates boarders.

The glass window commemorating the discovery of Holtermann’s nugget is in the foyer of the school’s BH Travers building.

souce: https://www.dailymail.co.